(Grupni Portret Sa Damom)

orig. Gruppenbild Mit Dame

I wanted to underline the kindness, the human warmth of a Germany represented by Leni Gruyten, a woman who knows how to love and give in a world where everyone takes. – Aleksandar Petrovic

| Co-Production: | Stella-Film, München, Les Artistes Associés, Paris, Cinéma 77 Betelinguns GMBH & Co. Produktions KG, ZDH, MAINZ. 1977 |

| Screenplay: | Aleksandar Petrović, after the novel by Nobel prize winner Heinrich Böll |

| Director: | Aleksandar Petrović |

| Set Design: | Vlastimir Gavrik, Reinhard Seigmund |

| Cinematography: | Pierre William Glenn |

| Art Director: | Vlastimir Gavrik |

| Producer: | Martin Hellstern, Hans Pflüger |

| Film Editing: | Marika Radvanyi, Agape von Dorstewitz |

| Choice of Music: | Aleksandar Petrović |

| Music: | Nightingale (Russian poem) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert |

| Cast: | Romy Schneider, Brad Dourif, Michel Galabru, Rudiger Vögler, Vadim Glowna, Richard Münch, Milena Dravić, Vitus Zeplichal, Velimir Bata Živojinović, Fritz Lichtenhahn, Rudolf Schündler, Gefion Helmke, Wolfgang Condrus, Peter Kern, Dieter Schidor, Isolde Barth, Milosav Aleksić, Elisabeth Bertram, Dragomir Gidra Bojanić, Max Buchsbaum, Connie Diem, Christian Hanft, Karl Heuer, Hannes Kaetner, Bettina Kenter, Joachim Kerzel, Heinz Lieven, Evelyn Meyka, Annie Monange, Dorothea Moritz, Károly Nagy, Witta Pohl, Kurt Raab, Alexander Radszun, Heidi Schaffrath, Erich Schwarz, Walter Tappe, Sabine Titze, Charlotte Adami, Carl Duering, Irmgard Först, Ingeborg Lapsien, Eva Ras, Manfred Tümmler |

Photo Gallery

More photosPlot Summary:

In 1966, in the cemetery of a German convent, red roses grow on the grave of Sister Rachel, a Jewish woman who died of hunger and cold in 1943. A miracle, or fraud? Leni Gruyten, a former student of the convent, is suspicious. Leni and Sister Rachel were very close. But Leni was expelled because of her rebellious ways…

We now find Leni at around 50 years old. She lives with a Turkish man in the same terrible conditions as when she lived with a Russian soldier during the war: forty years of a life defined by the tragic consequences of war.

Awards, honors, festivals :

- International Films Festival Cinema City, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2009 – Hommage to national auteur Aleksandar Sacha Petrović

- Documentaries Film Festival of Rennes, November (Special program), 1992

- FEST International Film Festival Belgrade, 1987

- Human Rights Film Festival Chicago, 1980

- Golden Reel, German Film Awards, 1977 – Romy Schneider – Best Performance as an Actress in a Leading Role – (Beste darstellerische Leistung Weibliche Hauptrolle)

- Outstanding feature film (Bester Spielfilm) German Film Awards, 1977

- Nominated for Palme d’Or (Best Film) XXXth Cannes Film Festival, 1977

- Nominated for the Prize of the Ecumenical XXXth Festival du film à Cannes, 1977

Press Excerpts:

A Yugoslavian filmmaker gives back the Germans their lost star: Romy Schneider

Translation of the newspaper article in the link above:

L’AURORE Guy Teisseire June 1st 1977

“If Leni’s hair was shorter and grayer, she could easily look 40 years old: however, she wears them long and wavy, creating an evident opposition between her juvenile hairdo and her aging face, making it seem like she is at least 50 years old…”

This is how Heinrich Böll describes the heroine of his novel Group Portrait with a Lady. This is her appearance: we discover the rest through testimonies from “informants” who speak with the author throughout a meticulous investigation, one that is almost manic where the novelist’s method replaces the novel itself in a typically cinematic process made popular by Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

Böll’s novel naturally lends itself to film. Petrovic, the filmmaker behind I Even Met Happy Gypsies, gets his hands on the adaptation rights the second that the novel is published. “Artistes Associés” tells him: “If you get Romy Schneider on board, we will finance this film.” Romy accepted…

In Berlin, in an old Reichstrasse hotel that was saved from the 1945 bombings, Petrovic creates Leni’s apartment: a grey haired Romy with tired wrinkled eyes (her character evolves over 25 years, her makeup changed a dozen times) drinks tea and eats biscuits. This is where her old friends, people who have witnessed her life, will gather once again. The furniture, the paintings, the trinkets, the table cloths seem like they haven’t changed in 40 years: a fossilized apartment populated by characters covered in spider webs…

It’s cold outside but the projectors and lights heat the set and the crew works in t-shirts. Amongst this chaos filled with actors from the United States (the incredible Brad Douriff, the young suicide victim from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, France… I find Michel Galabru (in the role of Pelzer, Leni’s loyal friend):

“My dear, I say my lines in French, the response is sometimes in German, sometimes in English, sometimes in Serbian, but rarely in my own language, for me and Annie Monange, the only French on the set. And we’re playing Germans, the American plays a Russian and the Serbs play Turks!”

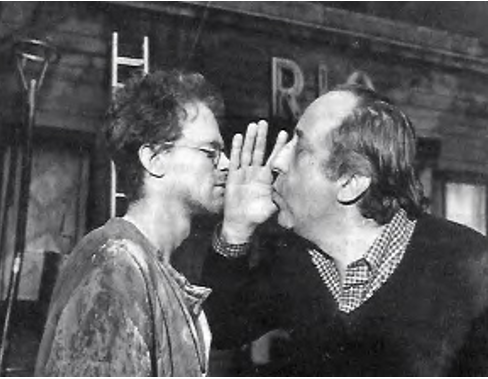

Petrovic chimes in: “We’re working like crazy: ten weeks of filming when we truly need 13…”

I must say that Petrovic cuts up his sequences quite a bit and changes shots for each line of dialogue.

“Why did I choose Galabru? I loved him in The Judge and the Assassin by Tavernier.”

I know he had some issues with Romy. She is always a little disoriented when working with a filmmaker that she doesn’t know and whose work ethic is pretty rough and rapid. But things worked out.

Petrovic went to Berlin to find poetry in the ruins, just like he will go in search of snow in Austria the next week:

“The story takes place in Cologne, but we could place it in any other martyr city. Here in Berlin, there is still a whole neighborhood of ruins that will soon be destroyed and restored. So we took it upon ourselves to help the demolition: some dynamite here and there and we find the face of war… It’s crucial to this film.

I wanted to show, as I think Böll did as well, that the Germans suffered during the war: it’s the tragedy of the executioners. For war is always lost, by the winners as well as the losers. And Léni’s character, one of the victims of this dark period in our global history, symbolizes this tragedy and shows its relevance today.

One thing attracted me the most in Heinrich Böll’s work: the mixture of the daily with the magical, which is very important to me in life.”

We already saw this in Petrovic’s I Even Met Happy Gypsies and The Master and Margarita. Petrovic thus found himself in communion with Böll who he, coincidentally, looks very much like.

L’AURORE-SPECTACLES – GUY TISSEIRE

Romy Schneider for ELLE

June 6, 1977

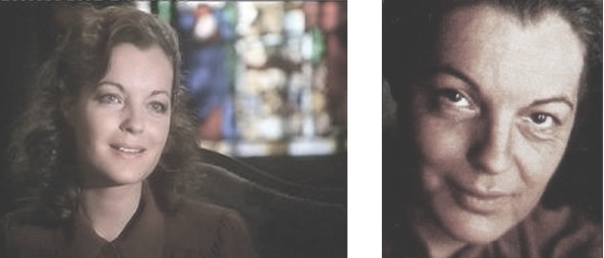

Thirty years — and two hours of makeup —separate these two images of Romy Schneider in Group Portrait with a Lady by Aleksandar Petrovic, presented at Cannes. Do you know how to face your age? Jacqueline Demonex in the next pages talks about the second image.

While filming, Romy Schneider greets me with sarcasm: “So, is she not too ugly this old Romy?” Since then, Romy has found her face again and the film represented Germany at Cannes. “But it’s terrible, staring at the mirror, to see ourselves as we will eventually be…” she confides. But with a swift flick of her hand, she erases her wrinkles and her worries: “The solution? My solution? To make sure I’m never bored again.”

GROUP PORTRAIT WITH A LADY

Cannes Official Selection

Cinematography – Philippe Carcassonne

Ten years after I Even Met Happy Gypsies, Aleksandar Petrovic comes back to Cannes with a film that includes Germans, French, Yugoslav, and Americans. He explains his multinational choice:

“… It seems that Petrovic has faith in the “global autonomy” of the film, meaning the idea that the film produces a rhythm, an emotion, a dramatic movement that are proper to the film itself. This requires an original linear system, a-chronological, the existence of an internal apprehension specific to each individual film. This is both its point and its limit. Petrovic conserved Heinrich Böll’s narrative structure, the enthusiastic scope of different phases of a plot, to try to establish a completely original logic whose terms, though more suggested than announced, end up creating a subtle lace of ideas and feelings.

Thus, Petrovic contrasts the hysterical and desperate faces of wartime Germany with the serene “giver of joy”, Leni Gruyten. Petrovic shows this without any didacticism, no matter how fond he is of his heroine. Group Portrait is a portrait that inverses the representation of narrative symbols: the decor becomes the intrigue, and the intrigue is in the decor. As opposed to making each plot point clear, he prefers to draw attention to long intense emotional moments. The scene with the coffee cup (that both Böll and Petrovic call “the coffee moment”) exercises this particular fascination: Romy Schneider cleans the cup over and over again, the object of her repulsion, thus giving the banality of domesticity a strong metaphorical embodiment. A corollary process is used later when the one-eyed soldier (the amazing Rudiger Vögler that marveled in two of Wim Wenders’ films) does one too many actions that attract attention and he ends up executed.

From this point of view, we find in Group Portrait a reference to a question of gratifying waiting, an effect of wonder paradoxically produced by the inevitable, widely evoked in literature, but that cinema has largely neglected, preferring a kind of spectacular surprise. This original journey and the almost impressionistic treatment of a slew of moral and metaphysical themes allow Petrovic to avoid the naive heaviness of “message” cinema, but don’t stop him from tripping on the classic traps of cinematic adaptation. It’s not about criticizing him for any infidelities to Böll’s novel (Böll collaborated on the script) — quite the contrary: he scrupulously respected the text, which ended up flattening the specific relief of his cinematic creation. I can’t help but think of what Peter Brook said about his King Lear adaptation: “What can be reproached the most in an objective adaptation is bias.”

Aleksandar Petrović on Group Portrait with Lady: In conversation with the Cinematographer

(interviewed by Philippe Carcassonne)

Cinematographer: We’re struck by the fractured structure of the film, of its story and rhythm. There’s a constant alternation between quick montages and slower scenes, the coffee scene for instance…

Aleksandar Petrović: I should tell you that in Böll’s novel, this scene is minimally described, there’s a fracture in the literary flow. I insisted on this “coffee moment” to dramatize the material manipulation of small objects. I see an interaction, a dialectical rapport between the rhythm and the dramaturgy, the arc of the scene. Similarly, I tried to free myself from the unit of style by enmeshing elements belonging to different genres. The style needs to be a function of the story and not the other way around, or else we risk falling into formality and sclerosis. I don’t think about “style” when I work. The importance lies in the feeling of truth. Style emerges from dramaturgy.

C: Did you find it difficult to work with actors from differing languages and backgrounds?

A.P.: Not at all! On the contrary, having Galabru, who speaks French, in front of Milena Dravić, who speaks Serbian, created original dynamism.

Michel Galabru: Absolutely! Filming “Group Portrait” was for me an incredible experience, I found the actors excellent. What counts more than the words themselves is the intonation, the music of the dialogue; it’s like an orchestra of multiple voices. The unfamiliar music of another language allows you to reinvent the dialogue.

C: Why did you choose Brad Douriff?

A.P.: The role of the prisoner is a passive, silent one, meaning it is very difficult. It needed an actor gifted with a strong presence, that can suggest emotion without necessarily expressing it. Douriff looks like he’s straight out of a Chekhov play: he’s the spitting image of a young intellectual Russian; he fits the character perfectly. That said, some interesting things happened because of the different schools and backgrounds that you spoke of earlier. Douriff comes from an American acting school, meaning the Russian one; for example, during the arrest scene, he asked me before shooting if we could give him his “military booklet”. I answered him that we won’t need it until later in the evening. Well, he insisted, he needed the booklet in his pocket! That’s peak identification. He would also always ask that his scene partners stay in front of him during the scene, even if they weren’t in the shot. Galabru and Douriff were shooting a scene and Douriff asked him: “Michel, would you like me to stay in front of you?” Galabru answered: “Why, you’re not in the shot…!” (laughter). In any case, these two schools complement each other, and what really counts is the actors’ talent.

C: You’ve now adapted Bulgakov and Böll; do you intend to keep adapting?

A.P.: I don’t have a preconceived system in place, I can’t really say; I would like to film a script based on a number of Isaac Babel’s novellas.

C: The scenes with the bombings are impressive; how did those happen?

A.P.: It turns out there was a whole neighborhood in Berlin that was going to be demolished; the Berlin Senate gave us permission to use it for the film. So we got in contact with the company in charge of demolishing, and we started lighting up houses, wall by wall. No one was hurt, which I’m quite proud of, because these kinds of scenes almost always lead to some accident. Furthermore, I have to say that I gained a considerable amount of personal experience in Belgrade during the war to know what to do during bombings and explosions.

C: Apparently, you did not tie yourself into making the story a little clearer…

A.P.: Everything is in the dialogue; with a little attention, I think we can understand everything. I don’t think I made a difficult film. Simply, people are used to following a film in continuity; so Group Portrait troubles them a little.

C: There are however numerous scenes (the coffee cup, the hotel scene) that are very nice, but bring nothing to the comprehension of the plot…

A.P.: If it’s in the film it’s important; every scene refers to not only the previous one but to the whole film. Böll’s novel is a hundred times more complicated; next to that, my film is a cartoon! (laughter). Seriously, I don’t think one needs to be more explicit; I don’t have any beliefs on the things I show, simply love and need to show them. I wanted to underline kindness, the human warmth of a certain Germany, represented by Leni Gruyten, a woman who knows how to love and give, at a time when everyone is taking. I think that Böll wanted to show his compatriots who behaved like thieves for 10 years that there was another way to live; Leni Gruyten is smiley, and calm, despite all of the sadness that falls on her. Yesterday at the press conference, a previously deported woman who had lived through this period, tortured in a camp, told me that in watching the film she discovered something unknown, a new Germany, and this gave her a feeling of being reborn. I received this comment as a gift.

A few years later: A resistance made of little things,La République des Livres, le Monde – Pierre Assouline

September 2, 2007

I saw this film back in 1977 but something tells me it would be worth seeing it again (this Monday night on France 3 at 11:25pm) with fresh eyes, the same as the novel that it is based on deserves a re-read. Aleksander Petrovic’s film and Heinrich Böll’s novel have the same title: Group Portrait with Lady (Gruppenbild mit Dame). In my memory of the film, that the author co-signed, I remember pieces by Mozart and Schubert (which ones?), the expressive traits of Romy Schneider in the role of the Berlin bourgeois who falls for a Russian prisoner, the surprising apparition of Michel Galabru, the beautiful lighting by Pierre William Glenn… As for the novel, a meditation on the recuperation and the mixing of ideas of the previously anti-nazis in a current Germany, it poses questions of identity (after the execution of her Russian lover, she falls for a Turk) resonating with more contemporary thoughts: it invites us to revisit Böll’s universe, the very missed writer of present-day Germany, and its hero victims suffering from History, its Christian morality, its revolt without a revolution, its wisdom and the respect that it inspired across the board.

Böll evoked the storyline of his novel as the fate of a woman that carries the weight of her country’s history from the 30s to the 70s on her shoulders. Looking back, Group Portrait with Lady seems a little dated; it seems as “out of fashion” as the political and social realities that it describes. It is saved not by its language but by the ethos of its community-oriented thesis of our societies, by the irony and the author’s technique, a montage, and a writing style that seem to be documentarian. And Leni, the heroine, is unforgettable in the little things, the loaded gestures, the minute expressions, the smallest of words with which she manifests resistance to the unacceptable. No big words, no big actions, no big gestures. Only details, but sometimes, that’s all you need.

Reviews:

Lost and found: Group Portrait with Lady

Like so many films by the great Yugoslavian director Aleksandar Petrovic, Group Portrait with Lady is off the radar. By Vlastimir Sudar

from our May 2012 issue

In the mid-1990s, a friend asked me to help track down the films of Aleksandar Petrovic (1929-1994), who had recently died, to screen at a possible retrospective in London. Petrovic was one of the greatest Yugoslav directors, best known for his influential and internationally acclaimed drama I Even Met Happy Gypsies (Skupljaci perja, 1967); since at that time in the 90s armed conflict was tearing Yugoslavia apart, perhaps the idea was to show the country in a different light from the then ubiquitous press coverage. While seeking out the films, I discovered for the first time that Petrovic had made a film outside Yugoslavia, the German/French co-production Group Portrait with Lady (Gruppenbild mit Dame, 1977). It’s a film that has haunted me ever since.

Group Portrait with Lady is an adaptation of the epic German novel that many believe played a key role in winning its writer Heinrich Böll the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1972. Like his other frequently adapted fellow countryman Günter Grass, Böll believed that a writer should operate as the conscience of his nation, and he never flinched from probing the most sensitive issues residing in its collective psyche – the rise of Nazism in the 1930s being the most obvious one. In his voluminous novel Böll explores the period from the rise of fascism to the mid-1960s, when Germany was at the height of its economic boom. Following several key characters, the writer finds some of the roots of fascism in what he sees as the repressively dogmatic culture of the Catholic church; more importantly, however, he emphasizes that the spirit powering the post-war economic boom and rapacious capitalist expansion was the same spirit Nazism thrived on.

It was clear to Böll, who collaborated on the script with the Petrovic, that the novel would have to be severely abridged for the screen. Petrovic took charge here, turning this into a World War II story focusing on young German woman Leni Gruyten (played by the Austrian-born star of French cinema, Romy Schneider) and her affairs with two soldiers during the war. In the pre-credits prologue to the film, Petrovic rescues one 1930s episode from the novel, set in the Catholic convent where young Leni was schooled and then expelled. He also sets the final scene in 1960s Germany – the main part of the film is one long flashback narrated by Leni’s wartime employer (played by another stalwart of French cinema, Michel Galabru).

Petrovic was criticized for including these brief snippets of the 1930s and the 1960s, which were seen as unnecessary appendixes inadvertently left hanging. But the director was a modernist who didn’t subscribe to the idea of fixed endings in his work; in this instance, too, he perhaps wanted to provide a framework for his group portrait of wartime Germany. Following the source novel, the rise of Nazism and the economic boom were the necessary bookends to the story.

The film’s portrayal of wartime Germany differs markedly from the usual stereotypes. Leni’s first boyfriend Erhard, an officer in the German army, and his younger brother Heinrich have nothing but a profound contempt for the Nazis and their vision of Germany. The two of them decide to escape to Sweden, but fail and are shot as deserters. Leni’s father, a rich industrialist, is exposed as a saboteur of the Reich, and promptly dispatched to a concentration camp. Leni, facing financial ruin, starts working at the local florist, busy making wreaths for dead German soldiers. As the shop can’t handle the demand, a Russian prisoner of war is brought to help out: Boris, a bespectacled young engineer who speaks fluent German (played by the American actor Brad Dourif). Slowly, Boris and Leni fall for each other, and she secures a fake German ID for him. But as Americans enter the city, Boris is arrested as a German soldier and dies in a French prisoner-of-war camp.

Petrovic directs the story as a low-key chamber piece, creating a quietly languid atmosphere, particularly in the scenes at the florist – albeit an atmosphere overshadowed by ominous events outside. Only in one scene does he throw down the gauntlet, foregrounding the war and revealing the film as a high-budget affair. Allied bombardments provide the spectacle as the city’s buildings are torn apart, but it’s a rapid montage of the overexposed faces of those who are bombed that’s most affecting – bringing home the horrors of the war in the most immediate way.

As Leni, Romy Schneider effortlessly embodies the character’s confident persona, which only slips during her breakdown in a bombed-out shelter. Brad Dourif – fresh from his breakthrough role in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) for another itinerant East European, Milos Forman – is also convincing as an intelligent and educated Russian, cautiously coy in a hostile environment. With Galabru and New German Cinema regular Rüdiger Vogler in supporting roles, the stellar international cast shows that this was a major arthouse affair, not without a whiff of Europudding about it. But Petrovic’s use of a multinational cast also has a point, expanding the book’s notion that wars between nations are futile affairs since nations themselves are fragile constructs – the film ends with a Russian buried in a German grave. So it’s a shame the Petrovic retrospective we researched never materialized, as screening this anti-war film by a Yugoslav director would have been all too timely in the mid-1990s, as his country fell apart.

Group Portrait with Lady premiered in Cannes in 1977, but is now completely unavailable, while all of Petrovic’s films remain very hard to come by even in his native Serbia. This is mainly because one of the largest studios of Socialist Yugoslavia – Avala Film in Belgrade, which produced his home-grown films – has been teetering on the edge of bankruptcy since the break-up of the country, and its precious back-catalog seems to be forgotten.

Group Portrait, however, is not in that treasure trove – in fact it had backing from United Artists. Considering its A-list arthouse cast, its disappearance below the radar is perplexing – all the more so since the frank manner in which it deals with the greatest tragedy of the 20th century makes it a searing reminder of the futility of armed conflicts.

http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/books/view-Book,id=4870/

What the newspapers said

“It’s appropriate that this portrait of the German war tragedy be done by a foreign helmer, not by a native one – for critical repercussions might possibly outweigh the integrity of the theme, and a backlash could result… Credits are top-notch, particularly Pierre-William Glenn’s lensing of the greenhouse to lend mood and atmosphere to the main line of the story. The performance by Romy Schneider is a good cut above her usual star status… Galabru as the greenhouse proprietor steals some scenes, but it’s he who gives the story its unity by drawing all the characters together. Dourif is more than credible as the starving Russian POW. United Artists may have a critical winner at Cannes.”

— Variety, 21 May 1977

Read more: http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/49856

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.